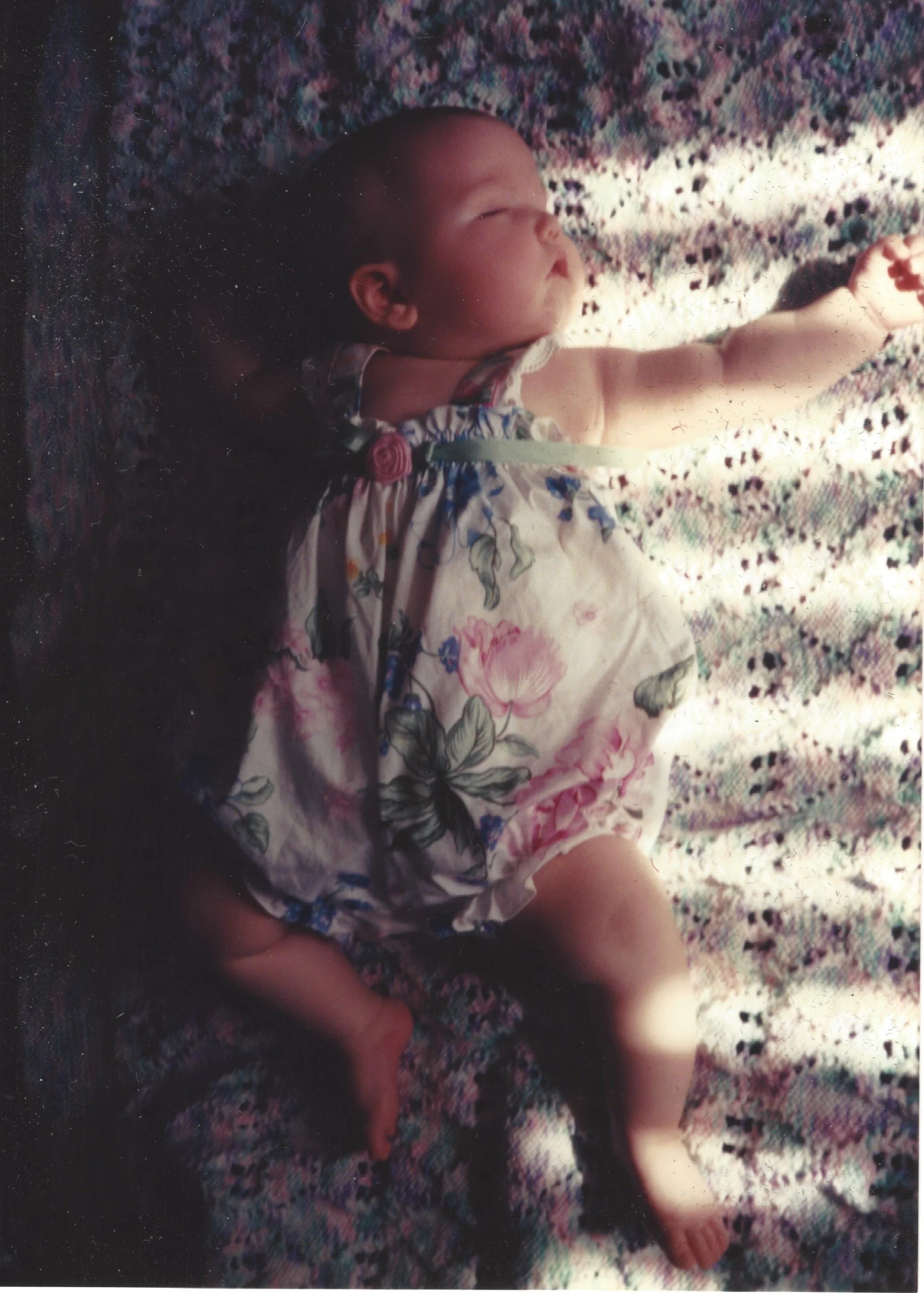

Katherine died fourteen years ago today. An acquaintance once told me, in response to our story, that at least young children do not understand death. "They do when they are dying themselves," I replied. At least Katherine did, as much as any of us ever do. Imagine having to face that kind of existential agony at age eight. As much as we hoped for more time for her, and as much as she struggled for every minute, I often wish she had died three weeks earlier, before her imminent death had become so clear to her, tormenting her with her own end, all the things she had left undone. She could have died at the very beginning of her final illness. Delirious with lack of sleep, I accidentally overdosed her on morphine, using the red-capped syringe to flush her port instead of the white. Immediately, she crumpled into herself and sunk into respiratory depression, her breathing labored and slow. We thought she would die. It was hours before I realized what had happened. The distraught young paramedics came and dosed her with an anti-narcotic. Riding in the ambulance, I was struck with how beautiful the sunrise was, how for everyone else on the road that early morning, it was just another day, while my world was ending. Carrying her into the hospital, she woke in my arms, after I thought I would never hear her voice again: "Mommy, where are we?" I comforted her, kissing her with the fervor of any mother regaining a lost child. And the inquiry was mercifully short. She was her own little self again, her brain uninjured.

Where am I going with this? I scarcely know. But this respite she had was both all too brief and too torturously long. She would wake in the morning after a night of struggling for breath, near death, and sigh, "Mommy, I survived the night." The morphine barely covered her bone pain. A fan blowing in her face helped her feel less the struggle to breathe. Great blue bruises accumulated as her circulation slowed and her platelets diminished. Her urine turned brown as her kidneys failed, and she lost the ability to swallow her medicine, however much she tried to comply. She mourned all she could not do on a beautiful June day and all she would never do again. She lamented all the years of life she would miss, which she would have enjoyed to the fullest, as she always did. She told me she loved me, in an ardent and anguished tone I will never forget. She had me record her last words to her brother and everyone else she loved. I hope we still have that tape, but I have never been able to bear listening to it again. I suppose I hope to impress on you all that although deaths from childhood cancer rarely make headlines, although they seem somehow silent and inevitable, they are both horribly violent and completely avoidable. Every day we do not rein in the chemical industry's business as usual, we are complicit in many more such deaths. And all the corporate profits and perfect lawns in the world cannot be worth my one darling Katherine.

Today, President Obama signed into law the Lautenberg Act, which puts some constraints on chemical production and use in the U.S. The Act is a start, but far from complete. And you can hardly expect those of us with children already dead to rejoice. But we can perhaps be soberly glad to think that with further regulation, maybe someday, no other parent will have to so needlessly bury a beloved child as a result of environmental chemicals.

To celebrate Katherine's memory, please do something to remedy this grave injustice: read more about the Lautenberg Act on the EDF website, work to eliminate pesticides and other chemicals, and, most important, vote the environment so that we can pass more such life-saving legislation.