Dr. Genoa Warner is an Assistant Professor in Chemistry and Environmental Science at the New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT). She has a very broad and interdisciplinary perspective. As we learned during the ECHO course, she started out in a green chemistry lab as an undergraduate at Yale, and then went on to Dr. Terry Collins’s lab to do sustainable chemistry in TAMLs for her PhD. For her post-doc, she ended up in a reproductive biology mouse lab with Dr. Jodi Flaws working on ovarian effects of endocrine disruptors. Dr. Joan Ruderman said she is “the broadest person in the course in terms of actually having gotten her feet wet in the three arms that the course addresses.”

Dr. Warner is remarkable for her precocity: she is young and energetic, and not only has she achieved much academically, but she also has three young children. She remarked how much she has been enjoying teaching and laying the foundation for what she hopes will be a long and successful career – like her own mentors, some of whom I have interviewed here.

One of the most striking things she described to me was how hard she works to try to protect her children from exposures – and the kinds of compromises and calculations she has to make when they want, for instance, a vinyl Barbie doll. I remember clearly myself compromises and calculations that every parent now in the know has to make, many of them quite painful and troubling. We both wish there were adequate regulation of environmental chemicals to protect children and to make every parent’s job a little easier. God knows it is hard enough without worrying about the thousands of chemicals each child is exposed to from pre-conception onward.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Figure 1: Dr. Genoa R. Warner

JMK: Hey, Genoa! Good to see you. I'm so glad we have a chance to talk a little more than we were able to at the ECHO seminar.

GRW: I hope I'm ready for this.

JMK: You can't really go wrong. There's so much I'd like to learn more about. You saw that I interviewed Terry Collins, and so it feels like I've gotten to know some of your work that way.

One of the reasons Joan [Ruderman] said that you'd be a very important person to talk to is your breadth. You did green chemistry as an undergrad at Yale. You did the TAMLs with Terry, and now you're researching reproductive health and endocrine-disrupting chemicals. So you have the full gamut on Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs), which I think is really helpful, right? I think even Terry having as much biology as he has makes him an outlier – that's so rare among chemistry folks.

So I'm sure you have a different perspective from people who've only been in one of those disciplines. That's what I do know about you. But I wondered if you have any stories about how you first got interested in problems of environmental chemicals generally, or endocrine-disrupting chemicals more specifically.

GRW: I can tell you the story. I was an undergrad chemistry major at Yale, and that is when it started. I became a chemistry major because I liked chemistry. I had picked out biophysics and biochemistry, but I liked the chemistry pre-reqs, organic and inorganic. I liked it, and I stayed. At that point, I was a Junior who needed to do research in my senior year, and so I just started emailing labs I was interested in: “Hello, I’m an undergrad. Do you have any space?” My interest was in something related to environment, and the first one that wrote me back was the Center for Green Chemistry and Green Engineering. And so I joined that lab first. I knew I was generally looking for environmental or sustainability-related chemistry research.

JMK: I don’t want to interrupt, but how did you know that you wanted the environmental part?

GRW: I don’t know. I’ve just always been interested in environment, sustainability – and also health. As a teenager, I remember reading and watching Fast Food Nation – and after that, I never touched a hamburger ever again (almost). Was it Fast Food Nation where they put the French fries in a jar? [It was Supersize Me.] One of my high-school teachers did that when we watched that. There was a movie – and a book that was similar.

It was an AP English composition class – we weren’t doing it for science – we were doing it for the presentation. But things like that really caught my attention. It stuck with me. I think that is a part of it because that is environmental health. I’ve always been interested generally in environmental stuff.

So I joined the Green Chemistry Lab partly by luck, and the project they gave me was taking waste materials – candlenut shells – like walnut shells, basically – and we would grind them up and extract these little oligomers out of them and characterize them, and that was all doing chemistry. But the point was to make something to replace BPA in can linings. It was an industry-funded project to try to find a BPA alternative.

Like most undergrads, I was just doing the science, not really understanding what the project was until later – when it clicked, and I realized – this is awesome!

Then I ended up going to work in Terry’s lab because the lab manager in The Green Chemistry lab had been done his PhD with Terry and said to me, “if this is what you want to do, I know just the person for you to talk to, and so he connected me with Terry.

JMK: Yes – it seems to work like that a lot of times. People don’t think about the fact that scientists are human too, and all those human connections really seem to matter.

GRW: Yes, and I really want to do the human connections as much as I can for my students, though I don’t have as many connections as I will someday. It made such a difference for someone to direct me towards Terry while applying for PhD programs because I didn’t really know what I was doing, but having talked with Terry, I knew I wanted to do that.

JMK: Yes – I think that kind of advice is very scarce – don’t just apply to a school. Find the person you want to work with for your PhD. I think very few undergraduates are told that – I wasn’t.

GRW: I wasn’t either. In terms of department-level advice, I didn’t get that – I was just introduced to Terry.

JMK: You can see the connection, the throughline between Terry's work and then going to endocrine-disrupting chemicals and then doing reproductive health. But was there anything that happened that really caught your attention, or was there certain research that you read? How did you make that connection?

GRW: Terry really enabled me to get into an endocrine-disruption rabbit hole and stay there, because, as a chemistry PhD student, I had to do all this chemistry coursework. We had to come up with proposals and give talks, and Terry was really free with allowing me to do what I was interested in. I'm sure it's not unusual for the students out of Terry's lab to talk about endocrine disruption and things within the chemistry department.

But within my cohort – I felt like an outlier compared to what other students were doing. But Terry is all for it. I was interested in toxicology specifically. These chemicals are cool that we were studying in water, and with an environment application, it’s like – I want to know more about these chemicals and health.

Then he took me to the Gordon Conference on endocrine disruption, which was where I met my postdoc mentor Jodi Flaws.

JMK: You all talk about the Gordon Conference in hushed tones, and I know some of the ECHO seminar students have been going to it.

GRW: Yes, it’s a great conference – the closest thing to an endocrine-disruption-wide field-level conference. Some people go to SOT (Society of Toxicology), some go to the Endocrine Society, but the Gordon Conference has been really awesome. Everyone is super welcoming and supportive of trainees.

JMK: It sounds like it's not so big so that you can all can get together and know each other. How many people typically attend the Gordon Conference?

GRW: Under 200 – not that big.

JMK: I find smaller conferences can be so much better.

Of course, I have looked around at some of your research. And by the way, I really enjoyed that you talked about nano- and microplastics (NMPs) with us – because that is such an emerging story. On the CHPAC, we've been working on a letter on plastics, and it is interesting to see how industry is really strongly opposing any action on plastics. Of course it is early days in the research, as far as health effects.

So you have that, and you have the work on EDCs, and work on the ovary and phthalates, and much else. But is there one thing that you would say you've done that you're most proud of so far?

GRW: You know the scope of what Pat [Hunt] and Joan have done, and I feel like just being a few years into my faculty career, it’s hopefully just a tiny blip in what will be in my career. The first couple of years is nothing. I’m doing my third-year review – and I have to write about research accomplishments that I am proud of. We’ve published a few papers, and each has had some insights, but nothing is super exciting.

I had a lot more to say than I thought I would in my mid-tenure review about the teaching that I’ve been doing, including ECHO. I am most proud so far about building a foundation – I am happy about where things are going. So I'm not too concerned about the fact that I don't feel like we've made any big research discoveries. I feel happy with where my lab is right now – to set us up to do a lot of things in the future.

JMK: Pat had a good foundation. She was all set to go, and then things happened, and her story is more serendipitous, probably, than most. But still, it seems like that's often the way, right?

GRW: Yes. We can only plan our research so much. And then sometimes you stumble on something and just have to follow it.

JMK: I was struck by how some of the discoveries about meiosis that Joan made are in just about every biology textbook ever since. Wow – that’s incredible. But they didn’t know how it would work out when they first started.

GRW: I loved reading Joan’s interview. It reminds me how much being faculty is stressful, but this isn’t everything, right? This is my mid-tenure review. There is so much more to come in the future.

JMK: Absolutely. And I so enjoyed ECHO – and seeing how you all are building a network of young incipient researchers who are thinking about this problem. I think so often we get divided into disciplines – and that’s often not problem-focused enough. I don’t know if we told you that our ECHO cohort is working on a commentary or editorial about the importance of interdisciplinarity.

Your research is so interesting. I find myself telling my students this sometimes: it's okay to say, this is really terrible, and it's an interesting problem; it can be both. But it's tough. And I just wonder if it's ever difficult for you. My book, of course, is focused on sick children. You're looking at infertility and other problems, and these things affect people's lives. A lot of these diseases are linked to these exposures. So I just wondered if this is ever difficult for you.

And when you're presenting this to students or anybody else you're talking to out in the world, how do you frame an issue that is super important, but also productive of anxiety?

GRW: Yes. This is a hard problem in the field, and I know that's why Pat and Joan have tried to have some hopeful sessions in ECHO, right? Because you can get really down thinking about all these things that we can't control.

You know, it's interesting how people have different approaches to that, too. The students would talk about this in my postdoc lab. Some of us try to do things in our personal lives to reduce exposures – mostly because it makes us feel better – we know rationally that it probably doesn't actually make a big difference, because there's so many things we can't control. But at least it helps us feel better about it. And some people say, no – I completely remove that from my personal life because that is how I need to function. And if I want to microwave my plastic container, then I'm going to, because it's convenient, and I'm not going to think about it.

And so I think it's helpful to remember that different people respond differently.

When I am talking about this with someone new, I do always try to remember back to how I felt when I first learned about this, because I think that's important just to remember those emotions because we get so deep in it that we forget what it's like the first time you learn about it. I remember being an undergrad, but most of it came when I took Terry's class in my first year of graduate school.

This does come up in my teaching. I teach toxicology at the graduate and undergraduate level, and this is all new stuff for some of them. Some are environmental science majors, some chemistry majors. They haven’t necessarily thought about environmental chemicals at all.

So the first thing I do in my undergrad class is I give them a chance to ask questions. At the end of every lecture, I hand out a little piece of paper and say, ask a question, and I'll answer it in the beginning of the next lecture, and they ask a lot of questions about exposures and health effects and protecting yourself. And so I address their concerns in that way – and I do have a list of different apps and websites where I can send people to try to address some of that. But it’s hard. Remembering that this is new for some people and that it can feel overwhelming is an important first step.

JMK: Yes. I wonder about your perspective as a chemist. I mean, so much good has been done. But so much harm has been done. Do you ever have students just say they don’t want to be in chemistry anymore? The chemical industry has been so careless about what they are putting out into the world.

GRW: A lot of my students don't know what they want to do. And actually, I think a lot about the ones who want to stay in chemistry, because what I want is to train them now to think about this stuff and to care about this stuff and then send them into chemistry so that they have this perspective and this knowledge, so that they know about environmental effects and EDCs. There are definitely some who want to have careers in NGOs or environmental science. But I think most about the ones I want to train to go into chemistry.

JMK: That makes sense. But I sometimes wonder. Do you think the good outweighs the bad of the entire chemical industry?

GRW: I know what you mean. And ugh! It’s hard to say. You think about medicine as an example – how much medicine has advanced because of all the different synthetic materials we have. I don’t think that is an argument you could win, especially with the general public, that it hasn’t been worth it or had significant advances.

I think there is a lot that has gone too far, like single-use plastics. We don’t need single-use plastics! We don’t. There are so many plastics that we could just get rid of, never use again, not make anymore. And that would be easy and would improve our health – and cost the chemical industry money. But we wouldn’t be losing important medical or technological advances because of that.

JMK: I just had my hip replaced, and I think it's high-density polyethylene (HDPE) in there, and I'm really glad to have it. I did the research ahead of time, and I do know that metal nanoparticles and microplastics will be migrating throughout my body. I'll still take it at my age. So it is interesting. I'm talking to Maricel [Maffini] later today, and she and Laura [Vandenberg] just had an editorial in Frontiers in Toxicology saying that we could just go back to that idea of essential uses. There are some essential uses important enough to warrant the damage. But, as you said, so much of what is actually produced is single-use plastics. It’s as though we have no sense of moderation. I was talking to Veena Singla about this – she's on the CHPAC now with me – I don't know if you know her. She has worked at the NRDC for quite a while. It's just so frustrating because the industry will say all the good that has come from plastics and chemicals and imply that gives them carte blanche, but, as you said, at least 75% of those plastics are not necessary. Maybe it's capitalism combined with chemistry that's the problem.

GRW: Yes, right! Yes, this is something I rant about to my students – the entire capitalism setup of sell first – an investor-driven, profit-driven – we just want to make our money! – system and how much that is ingrained in chemistry. That is a problem. Chemists are not trained to think about anything other than making something that does what you want it to do, and then being able to commercialize it.

I see it all the time, in academic chemistry as well. Academics will patent something and then start a new spin-off company. That’s all they think about. That is what I find frustrating. Terry is an outlier. Chemistry is hard to integrate into ECHO because chemists do not think about this stuff. They do not care about this stuff. Of course, there are people who are trying to make degradable polymers, and things like that, but that is still not enough.

We have seminars in our department. One speaker was talking about some chemical process. He wanted to make a particular probe to understand a reaction, and the hydrogens in the molecule were a problem. And so he had his students synthesize a fluorinated version of the compound, where they replaced every hydrogen with fluorines. Chemically, electronically, it did all the things he wanted it to do. They figured out their problem. I asked – you know you are making PFAS – have you thought about what you are doing here in the context of forever chemicals in the environment? He said it never occurred to him that this was a PFAS. We need more sustainability training. We need green chemistry not to suck. [We both laugh.]

JMK: Right?!

GRW: We need chemistry to be reclaimed, to be more broadly sustainability related. It needs to be part of education. And we need chemists not to be so snobby about environment and sustainability-related things as not chemistry or something – or as a subfield of chemistry.

JMK: I had a close view of this. My former husband was a PhD chemical engineer, and he had one biology class as an undergrad – and nothing ever again. He worked for BP and still works for an offshoot of BP. And people would look to him about the health hazards of manufactured chemicals! I see how good chemistry nerds aren’t trained to think about these things, and of course, because of our daughter, I made him think about these things.

Anyway, it’s a good story.

Did you say you have children?

GRW: I have three.

JMK: Wow – congratulations! That is awesome. That must also shape your view to some degree. I wonder if you could tell me a little bit about that, and how, once you have children, you tend to think differently about the whole world.

GRW: Yes – totally true. When you have children, you think differently about the world. I worried about chemical exposures a lot when I was pregnant because we know that is the most sensitive time. And I am a person who feels better about controlling or trying to control exposures. I don’t drink beverages out of aluminum cans – and they are everywhere these days. Now that I’m not pregnant or breastfeeding, I might occasionally drink from them if I am at a party where there is nothing else to drink. But when I was pregnant, I was like – absolutely not. I didn’t eat pizza I hadn’t made myself during pregnancy – because I know tomatoes come out of cans. There are all sorts of things like that. I bought a water purifier during my first pregnancy. I did a lot of things like that that made me feel better. I don’t know if they actually make a difference. But with kids, you think about it a lot more.

And it’s hard not to wonder. Is my youngest’s eczema related to something that we could control in some way? Or is it related to something that is not controllable? Is it related to an exposure? I know you think about this kind of stuff all the time.

JMK: Well, I do, and you know not as much was known then. I was pregnant with Katherine more than 30 years ago, and yet I was filtering my water. I got made fun of by my father in-law, but I was filtering my water diligently, and we thought we were doing all we could – the organic baby food – all the right things. We didn't know they were spraying chlorpyrifos right in our windows. And so yes, you're right – some of it may be controllable, and some is really not, at least not by individuals.

But I do think that caution is inbuilt to us – and adaptive. That's the mama alarm, right? If you know these risks, you should think about what is preventable. Not everything's controllable, but some things are, especially on a societal or community level. If only we had known they were spraying for mosquitos.

How old are your kids? Are they old enough that you communicate any of this to them?

GRW: They are 2, 5, and 7. With my oldest—there are a lot of things she wants to do or have. And I have to tell her, no – you can’t – it has bad chemicals in it. She wants to know what that means and what it will do to her. I attempt to give a second grade-level explanation. Sometimes she says she understands.

She wants certain little plastic toys – junk that is handed to kids all the time. A lot of that stuff comes home, and I throw it right in the trash, especially if it’s vinyl. You can’t keep choking hazards – button batteries, crappy little plastic things that I am sure are reeking all sorts of plasticizers. All that goes straight in the trash. It’s just another one of those things to worry about.

I hope my oldest will understand more as she gets older and will believe me. There is so much media out there that is not honest about these sorts of things.

JMK: Absolutely. I mean advertising alone. And then, influencers…. It’s hard. At least at that age you can control them a little bit more. But then yes, I'm sure you're thinking like I did that you don't want to be so stringent that they rebel when they get to be older.

GRW: Yes. I have given in on some things – does this exposure really make a difference? Or is it just me being hung up? I tried to maintain a policy for years that we did not have any hard plastic dolls. They are all vinyl. And then the Barbies appeared – because how can the Barbies not appear?

JMK: Right?

GRW: Our neighbor gave us some old toys. And then, all right, fine – we have the Barbies, but I’m not getting other dolls. And then they are at American-girl doll age. I looked it up until I could figure it out. I know exactly what plasticizer replacement is in these DEHP-free dolls. Are they really going to have so much plasticizer exposure from a doll that I need to say no to this when we buy so much plastic-wrapped food, right? It’s hard not to make that kind of probably logically faulty comparison when faced with the strong desire of the child for something. I said, “fine, you may have the doll – but don’t touch it.”

JMK: Yes. Right. [We both laugh.] Leave it on a shelf somewhere. I know – that is so hard. I remember with my daughter, we didn't do Barbies because I was a feminist. Instead, she got little Madeline dolls – 8-inch hard plastic dolls, so cute. I mean, the list of things that parents have to think about is so incredibly long. And you mentioned media. And that's a whole ‘nother thing, right? It's just so daunting. Maybe that's one reason fewer people are having kids – because it is a hard thing to just think of all the things you're supposed to protect your kids from because our regulatory system doesn't.

GRW: Yes. It shouldn’t be so much on us. But it is.

JMK: Yes. And it's very different to think in the abstract of protecting children. And then you have your own children. And then I thought very differently. I thought, what the heck have I done to myself now? I didn't expect to love my children as much as I did.

GRW: Yes. They really do change how you think about everything.

JMK: Absolutely. So, this question springs from what we were just talking about. If you could single-handedly recreate US policy regulating environmental chemicals, what would the policy look like? And then, thinking more realistically, how do we change going forward given the policy we do have?

GRW: I would want it not to be sell first, test later. We want more testing. That requires money, and nobody wants to pay that money. But in my dream world, we test things thoroughly. We have thorough tests for endocrine disruption – and that is one of the problems. With endocrine disruption, we don’t have a test, or even a small set of tests that work on everything.

We want to test low doses. We want to be more precautionary. That is the dream world. Also, broadly, in STEM, maybe everybody, should have some training in sustainability, so it doesn’t seem so outlandish to people that we are culturally more proactive about sustainability. Yes, testing costs money. But then it wouldn’t seem so egregious to ask a company or a designer to test something more than they do now.

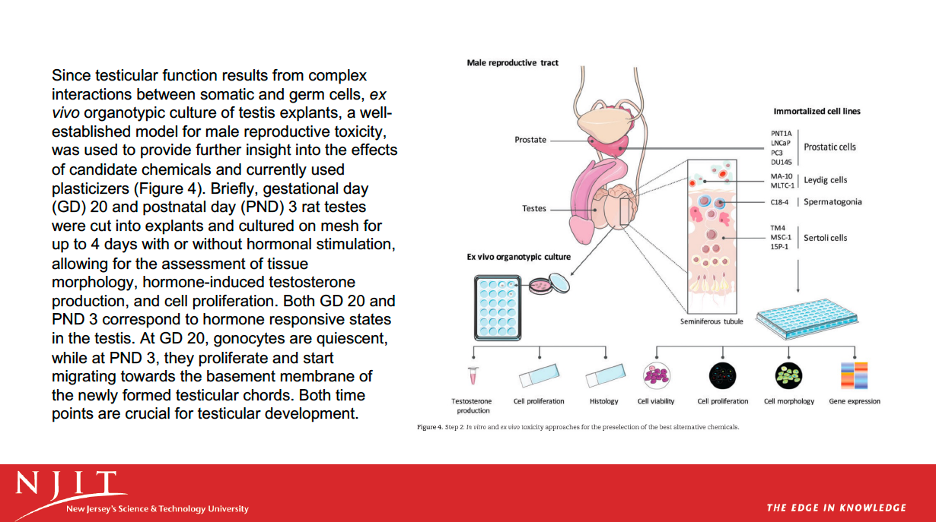

JMK: Yes. I was thinking – you gave a presentation on this at ECHO on this, didn't you? About the testing and safer chemical design?

GRW: Yes – a little bit.

JMK: If you don’t mind, maybe I will put a slide or two from that presentation in here because I think it’s not unimaginable that we would have a series of tests and run new chemicals through that on the front end. Wouldn’t that be great?

Figure 2: Warner from Schug et al. (2013). http://xlink.rsc.org/?DOI=c2gc35055f

Figure 3: Warner from Albert et al. (2018). http://academic.oup.com/toxsci/article/doi/10.1093/toxsci/kfx156/4060487/Identifying-Greener-and-Safer-Plasticizers-A-4Step

JMK: Given what we do have, which is so screwed up, do you have any ideas about how we could get to a point where it is better?

GRW: Yes. For endocrine disruption, we need to keep building the tests for adverse outcome pathways – figuring out what the appropriate tests are and the signatures to look for. We need to keep building it up until we get there.

JMK: At the EPA, there seems to be so much emphasis on NAMs (New Approach Methodologies).

GRW: The EPA is tough – there are really great, well-meaning people there who have done a lot of things, and yet collectively, the EPA hasn’t done very much. It’s hard. I don’t want to criticize, but what they have done just isn’t very much. They get hung up on things like alternative models and what fraction of chemicals that they said they were going to assess have they actually assessed.

And then one of my pet things that I'm interested in is alternative chemicals. One direction my research is going is alternative plasticizers so that when the phthalates come out of products and manufacturers claim, “This is phthalate-free,” they have an alternative. Usually, they put similar chemicals that could be worse in there.

This is where we need more testing. Something new is going in because what came out was bad, but there are no tests to make sure the new thing doesn’t have the same properties. Most are super similar chemicals – you change a couple of atoms a little bit, and it has similar properties, and they don’t test it. That’s how so many of the replacements come about.

I’m interested in the replacements. The EPA talk about all these different chemicals that they have run through TOX21 and other screens. These replacements aren’t in there. A lot of this seems to me kind of obvious. We put these chemicals in our products; they get in our bodies. They get metabolized. People can measure the metabolites and see how much humans are exposed to. Some of the metabolites of these chemicals – you can’t even buy a standard. If we want to study their toxicity, we have to synthesize the chemical first. That just shows how much work has to be done just to study them.

So I want to see more testing of new chemicals and of replacements. Chemical manufacturers don’t tell you what goes in there – they take one thing out and put something else in. We figure it out through things like the PlastChem database. Those researchers looked through extractions from plastics to see what different kinds of chemicals are in use – and they have a big database. I waded through that to find similar structures – and I found a bunch of alternatives of the type we are interested in. But we never would have known that those were in plastics if someone hadn’t gone out and actually measured what chemicals were coming out of these plastics.

JMK: I just remember Scott [Belcher] was so upset when Sharon Lerner's article on 3M came out during ECHO. I think he had been working on some of those very chemicals, trying to figure them out, and 3M knew all along what they were, that they were in all humans, and that they were toxic. But they made the researchers go through all kinds of hoops. They don’t have to share information. It’s nefarious.

GRW: There are so many stories about that – more coming out all the time – about companies hiding effects, hiding toxicity. Exxon Mobil and the California plastic lawsuit – recycling was not going to be efficient enough, yet they marketed recycling as a solution to our plastics problem. There are continually new stories, new stories, new stories.

I appreciate all the work that Laura has done on this and the presentations she gives. I talk about some of her papers in my class because I think it’s essential to learn about the context for these issues.

JMK: Yes – and I was really, really glad to get to talk to Laura as well! I feel so privileged to know you all.

I had just a little side question. Did you buy Terry's TAMLs product? I mean, I bought some. I said I was a company, and then I haven't tried it yet, but I might. Do you feel like you would just use that around your house if you had mold?

GRW: Yes. But okay – here’s my story. You bought a chemical that says on the package, NT-7? I made that! I designed that one.

JMK: Oh my gosh! You made that?!

GRW: Terry has the vision for the class of chemicals – I started substituting functional groups based on generally what he wanted to see, and I wasn't able to get everything in all the right places. And so I had tweaked the structure to be able to make something, and that is it. That was the something that I made. It was my PhD thesis that now you can go out and buy. And I actually probably have a vial of it in my desk, just in case I wanted to do future science with it.

JMK: I bought it, because, you know, usually I just would use baking soda and vinegar. But I have some mold going. I haven't had the guts to try it yet, because I'm usually like you. I'm as careful as I can be, but mold is not good for health either. And so that's so cool that you made it. I could see how chemical synthesis is interesting, before we knew how harmful so many chemicals were for health. I totally get it. It's very creative. It's incredible to be able to think of manipulating the very stuff of life, of existence, and creating new things.

GRW: Yes – chemistry is fun!

JMK: Okay. In your view, how would you answer the central question with which I'm occupied in really all my work? If we know we're poisoning our children, and we are destroying the only climate on the only planet that we know supports life, and we know there are probably solutions out there, some better than others, why are we not adopting them? How have we allowed this to happen, and how, as a society, are we continuing to turn a blind eye to it?

GRW: Oh, capitalism! Right? It's the money. It's the short-term personal gain. Everyone wants to make money and improve their lives and maybe pass it on to their children. But no one's thinking long term. Nobody wants to give up things now for five generations from now. The problem is our entire capitalism setup.

JMK: Yes.

GRW: The incentive is money and greed, and not long-term health or sustainability.

JMK: You knew enough to stop eating hamburgers. I mean, hamburgers are pretty tasty, but you're also super smart. So how do you persuade people? The broader society, I think, find it really hard right to go against these impulses that are built into us.

GRW: I think it's really hard. And I think that there probably have to be policy changes. The way things are now, nothing's going to happen organically. There have to be more restrictions and more laws.

I think long term there has to be better education. Maybe I say that because I'm an educator, because I believe that education is important, and I hope that we can influence the longer-term future by training people better. I hope to empower young people with knowledge about this stuff, so that when they grow up, they still think about it, and they care about it. And then, maybe we can start to reshape some things, but that will also have to come with some more aggressive policies.

JMK: Yeah, I'm an educator as well, and I share your hope. And I do feel like my students are so surprised to learn what I teach them, and a lot of them seem to believe me when I say knowledge is power. I agree. I think that's a hopeful thing – maybe even education on down to grade-school level.

You're going to see whether your kids get any of that pretty soon.

GRW: Right? I’m testing it out on them. We’ll see how the teenage years and the personal care products and things go.

JMK: Right? That is a tough one. You mentioned before changing the culture, and I think that's really hard to do. But maybe education is one way to do it. Any other thoughts on how to change the culture enough so that people think about the world in a different way?

GRW: I want to think that it’s possible we could do it. But I don’t know. I’m maybe jaded about that because American culture is not that at all. There’s just so much consumerism, and I don’t know how to actually fix it. I don't want to think about it too hard. I don't want to think about my exposures too hard, or I'll feel depressed about it.

JMK: Yes. And you know what? You're thinking about all the chemistry and the biology. You do that. And this is what I'm thinking about.

But I do think of how we changed culture around smoking. Now, we do have a regrettable substitution with vaping, and with that, we may have to start all over again. But that was something people changed the culture around – or drunk driving, or a few other things like that.

Okay, what do you think will be the status of children's health in the year 2050?

GRW: I don’t know – I think that there are a lot of things that have significantly improved in terms of children’s health – like cancer treatments have improved. I’m thinking about Katherine. Things like that will hopefully be more treatable by then. But I’m worried generally about everyone’s health – when we know that chemicals exposures are increasing, and plastic exposures and use are increasing. Plastic is not going anywhere other than sitting in the environment and in our bodies. So I’m a little pessimistic about the baseline level of health for everyone, not just children.

JMK: Not just children. Of course, every adult’s risk is greatest during the really vulnerable prenatal period and childhood. I think that’s a good message – if we help children, we help everybody. But yes.

I’m encouraged that you did have three children, as much as you know.

GRW: I do have three.

JMK: I'm afraid that I have talked my children out of having children – without meaning to, of course. I still think kids are just the best. It doesn't seem like an option to give up on humanity like that.

GRW: I know. I find that outlook hard to relate to personally because I love my children so much.

JMK: Yes. Me too.

So last question, is there anything that you would like to ask me about the project or about my experiences?

GRW: So what was interesting about how we met originally was that I came to ECHO three quarters of the way through, and so I missed all the introductions. So I met everybody but sort of indirectly, and so I feel like I've missed some context. I’ve read all your interviews, and I’ve read a bunch of your writing.

JMK: That’s kind!

GRW: I know that the book is about children's health, and that you are thinking about how it is socially based.

JMK: The first book is really about that big question, looking at the cultural context. The second book, Poisoning Children, for which I'm interviewing you, is really much more direct. It's pairing interviews with experts and literature reviews with children's stories, including Katherine’s.

I have a close friend whose child has autism, and I'm looking for stories of children suffering from asthma, birth defects, autoimmune disease, and climate-change impacts. And then I do literature reviews and interviews with the experts, healthcare providers and activists who are working on this problem. For me, to know that people were working on this all along has meant a lot to me, and I think it would to others. And then to actually get to talk to these researchers – they spend a lot of time in the lab! They don't often talk to the people whom their research is helping. I'm trying to bridge this to try to show first of all, that these exposures impact real people – including you, dear reader, potentially. And we know these things are true, even though the industry will try to keep that from your attention. And then also, I think it's a really hopeful thing that people like you are working on these problems.

I was really pleased. I had academic-ified the book proposal to get the contract. But then, once I started talking to my editor, he brought up the possibility of aiming for a broader audience. I want to get that crossover audience – not preach to the choir. I want new parents, maybe – or people who are thinking about becoming parents – to pick up the book. I want to help them protect their children, so they can help make change in the world. The culmination of the book will be a toolkit of what they can do, and how to try to make change.

GRW: You have two things that then jump out to me as challenges: the one that we talked about – how do you not scare people too much? And the other is how do you approach the nuance of not being able to know for sure what caused some kind of health impact? I know that in your case with Katherine, you are aware of a particular hazardous exposure, though you can’t know if there were two hits, in accordance with the two-hit hypothesis. You can’t know everything. But for most people, they don’t have that knowledge of a particular exposure like you do. So how do you approach that?

JMK: And some of that knowledge only came after her second exposure. So I know that I was exposed to chlorpyrifos in an apartment sprayed for roaches. It was all over our counters, and I cleaned it up. I had an acute reaction for months, and that was almost a year before I conceived Katherine. It was months at least before I conceived her. We moved beforehand because we knew – just in case we wanted to have a kid – we should avoid exposures.

Now, looking back, we know that that preconception exposure could have been quite important, in fact. And then we only knew after her second bone marrow transplant that they had been spraying chlorpyrifos for mosquitoes, and we could time mysterious illnesses in both children to those sprayings. I mean, you can never know for certain. So how I thread the needle is to say that we have every reason to believe that this was the major factor in her cancer, and I try to acknowledge, too, that most parents will never know what caused their child’s cancer, even though environment likely played a role. They will just never know.

One of my best friend’s son is featured in chapter 2, autism. We met because her daughter also had cancer, and she believes that there was a pesticide exposure where she was working as a psychologist in Cook County Hospital. At the same time her daughter was diagnosed with cancer, she gave birth to a second child who, very early on, it became clear, had autism, and she worries that that exposure may have influenced both of those outcomes. And you can't know – not completely. But there is reason to be persuaded when you do know about the exposures. And we do know that on the population level, risk is increased. We have animal data and in vitro data to back this up, as well as biological plausibility and the other Bradford Hill criteria.

Most parents who have a kid who is seriously affected want to know why. Right? I think it's just built in. I remember someone saying, “Well, why do you care what caused it? You should just focus on treatment.” I said, I want to know because she's still alive, and I want to prevent other exposures and the chance of relapse. And because I have other children whom I want to protect.

I actually think it is well worth the energy you're putting into thinking about your children's exposures. And I agree with you to balance choices. But I think it is worth that energy. If more people, even just parents, were doing that, then we would say, “Hey, wait a minute! Why do I have to think of a hundred million things that could be affecting my child when we could just try to protect everybody?”

GRW: Right? It's a super important message, and I'm excited to hear that your book contract went through.

JMK: Thanks!

GRW: One of the things I do in my classes with undergrads is we read popular science books for the general public. We read Our Stolen Future and the recent one To Dye For – about dyes and textile exposures – very much books written for the general public about toxicology and environmental health. I’m also on the lookout for new books. They really like this assignment because they don’t read non-textbook books very frequently in college – it’s a break – and interesting. And then they present them to the class. We talk about the communication aspect of the field. I like the idea of pitching it more for general audiences because it’s a really important topic, and people need to know.

JMK: I remember being a young science student and just feeling like I didn't know what it was for, and especially things like chemistry classes. You're memorizing so much. I actually liked organic chemistry better because it was the science of life. And you could start to see connections like, “oh, you can synthesize banana flavor?” Well, that's pretty cool, right? I could start to see some connections. But I think that's really smart that you do that with your students so that they're getting the very, very particular toxicology, but also more of a framework and the communication piece.

GRW: I totally stole that idea from Terry, who assigns the students in his class to read. I don’t know if he does whole books – he did excerpts of books in my day. We read the first two chapters of Deceit and Denial – about vinyl chloride – that’s a pretty dense book. But I love the idea of reading “real books.” And so far, it’s worked really well.

JMK: That's so good. Did you see the headline about Columbia students? Apparently, a high proportion of these very, very good students had never read a complete book by the time they arrived as undergrads.

GRW: Wow. Okay. I'm making sure a small population of the NJIT students have read a book – assuming that they actually read the book. I think they do.

JMK: I bet they do.

Well, it's been such a pleasure talking to you. I really appreciate the time so much, and I will probably be doing this over the weekend, and it may take me a few weeks to get the blog drafted, and then I'll send it by you to make sure it passes muster, and then post it.

GRW: Okay, sounds good. I’m honored to be included. You know, starting out in this field as a student, I still feel that funny thing…. Sure, I'm a professor now, but all the people who were my mentors – they're still my mentors. And so I'm very aware of how I feel like a student a lot.

JMK: Ha! Well, I will tell you – this is a problem that solves itself.

GRW: I see. You’re right.

JMK: Anyway, such a such a pleasure to talk with you, and I hope you have a wonderful weekend. Enjoy those kiddos!

GRW: Thanks. I will.