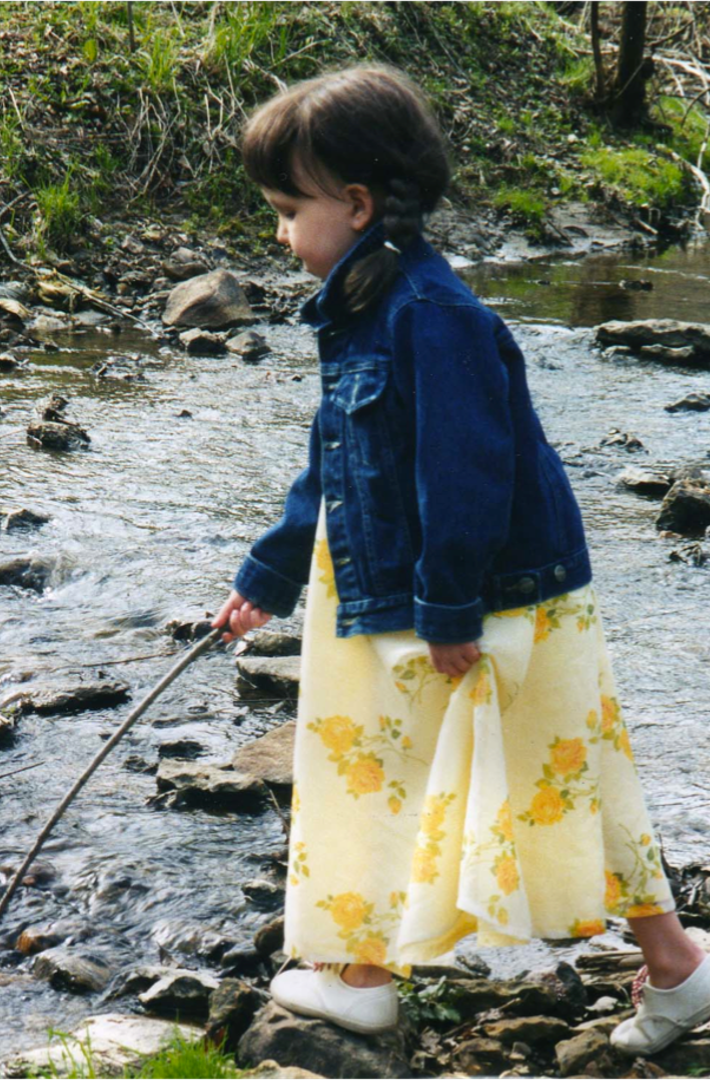

The following is a conference paper delivered June 22, 2023, the twenty-first anniversary of my daughter's death, at the 1HOPE conference at Benedictine University.

I don’t often talk about how I first became passionately involved in environmental issues. Some of you know that my brilliant beloved daughter Katherine was diagnosed with leukemia we have every reason to believe was caused by her unwitting exposure to pesticides via mosquito spraying. She died of her disease twenty-one years ago today. She has missed most of her life. When I hear Greta Thunberg say, “How dare you?! You say you love your children above all else, yet you steal our future before our very eyes,” I hear my daughter’s reaction to city council members who wanted to keep spraying the chemicals that caused her cancer: “Mommy,” she said, “don’t they love their children?” These voices haunt us. They should. “If you choose to fail us, Greta says, we will never forgive you.” My daughter, who is dead, and Greta Thunberg, who is alive, ask, why do you choose to fail us?[i]

The issue of environmental intergenerational injustice is poignant and urgent, and it extends not only to climate change, though that is the foremost threat, but also to inherited, bioaccumulated environmental toxics, epigenetic change, reduced biodiversity, extinct species, and lost ecosystems. Increasingly, many are joining their voices in protest of the depredations committed by my and my parents’ generations against my children’s and their children’s generations. Pope Francis was clear in his 2015 encyclical Laudato Si’ that the sins of one generation against another are sins indeed, that transgressions against Mother Earth are crimes against all her children in our shared and only home. This idea of human community is captured, too, in the Catholic idea of the Communion of Saints – a community of people living, dead, and yet to come. Far from considering future generations, we do not even consider our own immediate descendants. And I wonder – when we speak of future generations suffering from our spoliation of nature, are we still thinking of far-off unborn people? I would argue that we should think instead of the futures of young people today, people we know and love, children for whom we are willing to sacrifice almost anything.

A recent book, What We Owe the Future, by the philosopher William MacAskill ponders generational injustice far into the future. One of his best insights is that we must first focus people on the moral rightness of the cause, and then allow people to find various ways to achieve that cause. The ethical argument is central. Native American and other Indigenous peoples have long staked their values on the principles of honoring future generations with right-thinking decisions: heck, Seventh Generation dish soap manages to capture this concept, drawn from Iroquois belief. The fuller text from the Constitution of the Iroquois Nation emphasizes the importance of good leadership into the future:

We now do crown you with the sacred emblem of the deer's antlers, the emblem of your Lordship. You shall now become a mentor of the people of the Five Nations. The thickness of your skin shall be seven spans — which is to say that you shall be proof against anger, offensive actions, and criticism. [...] Look and listen for the welfare of the whole people and have always in view not only the present but also the coming generations, even those whose faces are yet beneath the surface of the ground -- the unborn of the future Nation.[ii]

This passage implores leaders to resist the temptations of contemporary popularity and to remain impervious to criticism so as to serve the common good of all humans, even those yet unborn. So why does this seem such a thorny ethical issue for contemporary Western, and particularly American, society? How is it that our laws and policies are not built to consider these kinds of injustices? Why are we systematically destroying the ecosystems upon which all life depends? Is it the short-term, quarterly or annual business cycle? The transient attention spans cultivated by TV, the internet, and social media (the medium is the message)? The frivolity of a culture that has relinquished attention to quality evidence, trusted authority, and truth itself? I will briefly contemplate the debt we owe future generations, particularly in the area of environmental sustainability, and will consider pragmatic ways to address inequity among generations in regard to the environment.

The UN has been focused on this problem of generational injustice for years (UNICEF 2012), as have philosophers and ethicists (Meyer 2021), and yet the idea has not had wide currency in the West until very recently. The Fridays for Future (FFF) activists, the group Greta Thunberg and others initiated, have been instrumental in getting this notion into the wider political discourse (Knappe and Renn 2022). As MacAskill argues, future people matter morally; and the morals we lock in now are highly contingent and could have long-continuing effects (his example is abolitionism). Just as it should not matter where harm happens – the life of a child in Rwanda should have the same moral value as a child in Illinois – it should not matter when (2022). There is overlap between intergenerational injustice and environmental injustice: where environmental justice principles recognize that for too long, toxic waste and climate risk has been ladened onto those already most disadvantaged and least able to speak up in society, intergenerational injustice recognizes that children today and unborn generations in the future are the most radically disenfranchised as this generation heaps burdens upon their own children and those to come. Only youth, but not young children and obviously not the unborn, can make claims against destructive actions today that necessarily entail destructive consequences in the future. Groups of young activists – globally (Rogers 2023), federally in Juliana v. United States (2020), and more recently in Montana – have done just that: sued the government for “willfully ignor[ing] the dangers of climate-changing policies”…that deprive them of their right to a “stable climate system capable of sustaining human life” (Mindock 2023). Our Children’s Trust has repeated this action in states around the U.S. Success in such lawsuits has been extremely limited, but gradually, ethical inroads are being made.

Effective altruism, an earlier incarnation of the longtermism MacAskill argues for, focuses on the most rational ways to help others, but many of its adherents have gone astray in thinking that the best way to help others is to plunge headlong into capitalism to raise the money to help others,[iii] to allay poverty in the short term, when a much more fundamental change of world systems will be necessary to head off the worst consequences of climate change and biodegradation. MacAskill emphasizes extinction threats like pandemics and AI but seems to me to underestimate climate change and environmental degradation. It is easy to do this given the staggering overlapping risks of exposures and disasters, cascading consequences, synergistic effects, and political destabilization that they are bringing. It is difficult to conceptualize the total impact of all we have altered in ecological systems. It is not just climate change but also forever chemicals like PFAS, micro- and nano-plastics that will perdure into the foreseeable future, bioaccumulating and biomagnifying through generations, along with losses in biodiversity that may not be recuperable.

One of the most hopeful changes in recent years has been a plethora of youth environmental leaders, building on the success of Thunberg and others. The EPA recently initiated a youth leadership team (2023). These youth leaders represent not only their own generation, which is surely feeling the impacts of a degraded planet already, but also all the generations to come, their children’s children’s children and on down. Henrike Knappe and Orwin Renn argue that these groups have succeeded in framing intergenerational injustice as a “concrete political demand”: “younger generations perceive themselves as the legitimate representatives of future generations, who insist upon justice and fairness” (2022). Furthermore, they point out that appeals to unborn generations can leave out those young people already born but facing a grim future because of the actions of their parents and grandparents and argue that they should be considered the legitimate voice of future generations.

In addition to the FFF, long-standing groups of young activists include the UN Major Group for Children and Youth (MGCY), UNICEF, C40, and 350.org; most of these groups employ the term generational justice, including intersectional perspectives. At one point, members of the MGCY called themselves “50% of the population [but] 100% of the future” and demanded a UN commissioner for future generations (Knappe and Renn 2022). This is an idea picked up by Kim Stanley Robinson in his 2020 book Ministry for the Future. Although this novel begins with the deaths of tens of millions of people in India from a heat wave, it is ultimately anti-dystopian in its imagination of a complete reforging of capitalist society via an intergovernmental UN ministry representing angry young people and vaguely allied with ecoterrorists. As with much of the emerging field of Cli-Fi, such fictions tend to run into themselves, to grow into reality not long after publication dates. There is a way in which, with climate change, consequences are here much sooner than expected, no longer imagined. These youth activists personify future generations now; they concretize the abstract and remind older people that time has run out. Some young activists are invoking a “Last Judgment,” a time in the near future at which today’s adults will be condemned for their failures to act (Rogers 2023).

It's hopeful that the Biden administration has focused the EPA on environmental injustice – finally. Among the injustices we must confront should be the issue of intergenerational environmental injustice. I am currently serving on the climate change work group for the Children’s Health Protection Advisory Committee to the EPA (CHPAC), and I am trying to work this ethical claim into the language of the advisory letter right now: intergenerational injustice is a subset of environmental injustice. Current generations are perpetrating a crime against younger and future generations unimaginable in scale; this despite claiming to love our children.

Pace MacAskill’s long-termism argument; we are not even looking at the distant future in the environmental impacts we are seeing on our children, our grandchildren. While I agree with the arguments of long-termism, I think it is only really important in its arguments about the ethics, the duty towards generations unborn. Such a distant appeal as MacAskill makes – hundreds of thousands, even millions of years – is not required, given how perilous the near-term future appears with impending environmental and technological threats – and such a claim can create the illusion that we necessarily have thousands of years. Furthermore, if we do succeed in locking in the right moral values in regard to the environment and future generations, current trends of environmental depletion could reverse relatively quickly, at least if we are lucky. It’s the next hundred years we should focus on most squarely, not the next million.[iv]

The call for just futures has gained currency in climate change discourse. What is too infrequently recognized are the overlapping impacts of the chemical consequences of our fossil fuel addictions. The fossil fuel industry’s new attempt at greenwashing is to bill plastics as an alternate, climate-friendlier destination for their product (Tabuchi 2022). But nothing could be further from the truth. Not only are microplastics being newly recognized as ubiquitous, toxic to human cells and growth, and accumulating at a rate that imperils future generations in unknown and likely permanent ways – from conception onward. Plastics also have a significant toxic AND climate footprint themselves, during creation, reprocessing, and disposal.[v] It is unclear which message will win out – the false, insidious narrative of corporations complacently destroying all of humanity, present and future – or the moral imperatives shouted in the public square by our youngest voices. But I know which message every person of good conscience should elevate. In this case, the truth is simple and comes out of the mouths of babes.

References

Beyond Plastics. 2023. The New Coal: Plastics and Climate Change. https://www.beyondplastics.org/plastics-and-climate

Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL). 2022. “Fueling Plastics: Series Examines Deep Linkages between the Fossil Fuels and Plastics Industries, and the Products They Produce. https://www.ciel.org/reports/fuelingplastics/

Children’s Health Protection Advisory Committee to the EPA (CHPAC). 2023. Personal communication.

Collaborative for Health & Environment (CHE). 2023. The Chemical Footprint of a Plastic Bottle. June 8, 2023. https://www.healthandenvironment.org/webinars/96691

Defend Our Health. 2023. Join the Fight to Prevent Plastic Pollution. https://defendourhealth.org/campaigns/plastic-pollution/

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 2023. “Establishment of National Environmental Youth Advisory Council.” Federal Register, May 18, 2023. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/05/18/2023-10572/establishment-of-national-environmental-youth-advisory-council

Gabriel, Iason. 2017. “Effective Altruism and Its Critics.” Journal Applied Philosophy 34: 457-473. https://www.academia.edu/13786913/Effective_Altruism_and_Its_Critics_Journal_of_Applied_Philosophy_2017_

Juliana v. United States. 2020. “Juliana v. United States – 947 F.3d 1159 (9th Cir. 2020).” LexisNexus Case Brief. https://www.lexisnexis.com/community/casebrief/p/casebrief-juliana-v-united-states

Knappe, Henrike, and Ortwin Renn. 2022. “Politicization of Intergenerational Justice: How Youth Actors Translate Sustainable Futures.” European Journal of Futures Research 10 (6). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40309-022-00194-7

Leiter, Brian. 2015. “Effective Altruist Philosophers.” Leiter Reports, June 22, 2015. https://leiterreports.typepad.com/blog/2015/06/effective-altruist-philosophers.html

MacAskill, William. 2022. What We Owe the Future. New York: Basic Books.

Meyer, Lukas. 2021. “Intergenerational Justice.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2021 Edition). https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/justice-intergenerational/

Mindock, Clark. “Youth Plaintiffs Get Another Shot to Bring Climate Change Lawsuit.” Reuters, June 1, 2023. https://www.reuters.com/legal/government/youth-plaintiffs-get-another-shot-bring-climate-change-lawsuit-2023-06-02/

Newitz, Annalee. 2014. Scatter, Adapt, and Remember: How Humans Will Survive a Mass Extinction. Albany, NY: Anchor Publishing.

Rogers, Nicole. 2023. “Intergenerational Climate Justice in the Courtroom.” Australian Humanities Journal 71: 96-103.

Rubenstein, Jennifer. 2016. “The Lessons of Effective Altruism.” Ethics & International Affairs 30: 511-526. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/ethics-and-international-affairs/article/lessons-of-effective-altruism/0C716CFD3FDCAF7BBC2CE99384C9B3F2

Srinivasan, Amia. 2015. “Stop the Robot Apocalypse.” London Review of Books 37 (18). https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v37/n18/amia-srinivasan/stop-the-robot-apocalypse

Tabuchi, Hiroko. 2022. “How Fashion Giants Recast Plastic as Good for the Planet.” New York Times, June 12, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/12/climate/vegan-leather-synthetics-fashion-industry.html

Unicef. 2012. Climate Change and Intergenerational Justice. https://www.unicef-irc.org/article/920-climate-change-and-intergenerational-justice.html

[i] Greta Thunberg. “You Are Stealing Our Future.” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HzeekxtyFOY

[ii] Constitution of the Iroquois Nation. https://cscie12.dce.harvard.edu/ssi/iroquois/simple/2.shtml

[iii] These criticisms have been leveled by an array of critics, including Jennifer Rubenstein, Iason Gabriel, Brian Leiter, and Amia Srinavasan.

[iv] See also Annalee Newitz’s witty and refreshing book, Scatter, Adapt, and Remember: How Humans Will Survive a Mass Extinction. She also argues for a million-year future for humankind.

[v] For more information on the climate and chemical footprints of plastics, see CHE (2023), CIEL (2022), Defend Our Health (2023), and Beyond Plastics (2023).